Put yourself in the cleats of a high school baseball player with aspirations of playing at a D1 program, and using that as a springboard to get the attention of big league scouts so that one day you could be drafted into an MLB organization. Then imagine that your season was taken away with no promise of any additional regular season games, no showcases, and no chances at all to raise your profile. Unfortunately this describes a huge number of high school athletes in 2020, and for Max Soliz Jr., he was one of the players that faced an uncertain future.

As a player that prides himself on his ability to outwork the competition, Coronavirus hit Soliz Jr. particularly hard. He’d verbally committed to play at Arkansas, but without a firm offer in hand, he knew that he still had to continue to improve to earn his spot in the lineup. But without the chance to do it out on the field, there weren’t any clear next steps.

“Kids may not understand that when you get a verbal commitment, it’s not a guarantee that you’re even going to walk on campus and have an actual scholarship. And most parents probably don’t even understand that. The key is that you have to continuously improve, and even then, colleges recruit multiple athletes at the same position to see who works out best.” – Max Soliz Sr.

Even armed with this knowledge, it didn’t give the Soliz family an inherent leg up on their potential competition. Soliz Jr. wasn’t allowed to head back to Nashville to train with his hitting coach; his high school wasn’t allowing students to work out together in any capacity; and while Soliz Sr. was able to throw some batting practice to his son, in his own words, “I don’t have a great arm so it’s hard to pitch well enough for him to try and execute what he’s hunting, which doesn’t ever allow him to get comfortable at the plate.” Even if Soliz Sr. did have a better arm, they both knew that it wouldn’t come close to simulating what happens at the plate in a real game.

“He’d have games where he wasn’t getting fastballs anymore, so having to adjust to a slider or a curveball and understanding the timing and the rhythm of that, it was something we couldn’t practice at home. Without the chance to face a curveball or slider that he’d end up seeing, or the velocity he’d end up seeing, it was a big concern.”

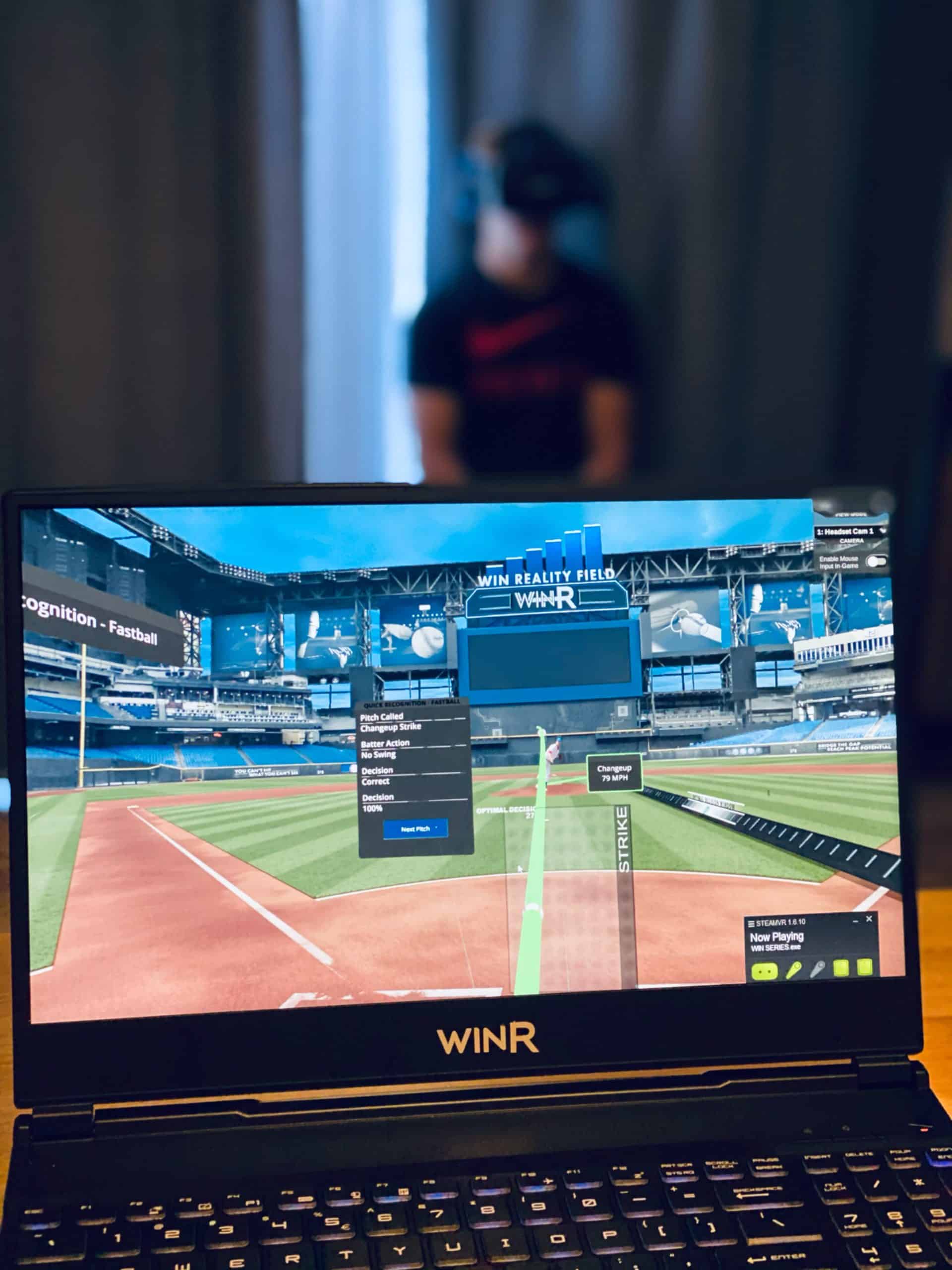

Taking all of this into consideration, the father and son team sought out alternatives to the traditional training methods, and happened to come across WIN Reality. By chance, they were in the same town as one of the representatives for WIN, and got a personalized demo of the product. Once he stepped into the virtual reality (VR) environment himself, Soliz Sr. knew he had to pull the trigger, and bought a system on the spot.